Big Blue Marble by Raima Larter

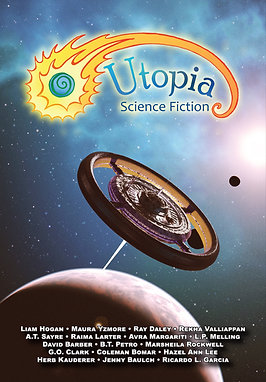

June 2021 | Utopia Science Fiction Magazine

“Every year on the Fourth of July, Stewart’s family packed up their beach umbrella and towels and headed to the Jersey Shore. They’d spend the day swimming and waiting for the fireworks to start.

Some things have changed over the years. His little sister, Ruth, is now part of the July 4th tradition, for one thing. Plus, it’s not the same seashore. Not even the same ocean, but Dad says the Sea of Tranquility is just as good. Stewart is not convinced.

“Tranquility has a better seashore than Earth,” Dad says. “The salinity is carefully controlled, and the temperature too! Plus, no nasty jellyfish to sting your feet. No sharks!”

“I guess,” Stewart grumbles. “But it won’t be the same with that stupid plastic dome overhead.”

“It’s not plastic, Stewart. It’s transparent silicon carbide, super strong and coated with conductive thin films. The fireworks are spectacular here, son! Computer-enhanced wonder. What could be better?”

Early on the morning of the 4th, Mom packs their umbrellas and towels and a picnic lunch, while Dad gets Ruthie into her space suit and helps Stewart on with his. The rover that will take them from the apartment dome to the seashore dome is supposed to be airtight, but no one trusts it, even for the short ride.

They clamber into the rover and it heads out, bouncing into the low gravity of the air lock. The inside door shuts and the outside door whooshes open, and then they’re off, careening over ruts and tiny craters.

“Oh my god!” Ruthie shouts. “We’re gonna crash!”

“No we’re not, sweetie,” Mom says. “The driver is very experienced.”

Stewart can hear his mom and sister through the radio in his helmet, but he can also hear everyone else, and they’re all jabbering at once. It’s a nightmare, like everything about this place.

Dad says it’s better here, even though he’s clearly wrong. It’s not better, despite what Dad had promised months before. That was when he announced they would all board a rocket ship and leave the Earth. They would be pioneers, Dad said, the second wave of lunar colonists.

The riots had been going on for weeks by then. Stewart saw them on the vid screen, at least when Mom let him watch. They waxed and waned, like the phases of the moon, sometimes almost stopping altogether, but there was always some event, some infuriating thing that re-ignited the blaze.

“But Dad — why do we have to leave?” Stewart complained.

“It’s the fires, Stew,” Dad said. “They’ve gotten too close to our neighborhood. We have to get you and Ruthie out of here.”

Stewart knew, because Dad explained it many times, that flame is the light produced by a chemical reaction. “It’s called oxidation, Stewie,” Dad always said. “It happens in your body, too, turning food into energy.”

And rage into dumpster fires, Stewie thought, watching the news of another major city in flames, this time someone else’s city, not theirs.

Dad said the enemy watches the people, sees the people’s anger and harnesses it for its own purposes. The enemy pits neighbor against neighbor, brother against brother, igniting a war fought without soldiers. The enemy is like that, turning a people against themselves. “It weakens their country,” Dad said. “It’s the perfect weapon.”

“But who is the enemy, Dad?”

“Not who. What. The enemy is a clash of ideologies. The people of this land were already attacking their own country. The enemy saw it happening and fanned the flames. It’s got to stop, but that’s never going to happen. People are always going to be people.”

Mom nodded in agreement, but Stewart knew all along where this was heading. What he didn’t understand, and still doesn’t, is why it had to be this way. Why did they have to leave their home just because other people can’t get along?

Two days later, the sleek rocket rose on a column of flame, roaring towards orbit as the crowd hooted below. Dougie and Harold and Jack all said they would come to watch, to say good-bye, but Stewart wasn’t allowed to see anyone after they were put in quarantine.

He was strapped into a padded seat and couldn’t move anything except his hands and his head. If he craned his neck around toward the portal, he could see the flames from the first stage. Eight and a half minutes into the flight, a flare burst sideways from near the tail of the rocket, freeing the first stage and igniting the second engine.

Stewart punched a fist into the air. “Woo hoo!”

Dad grinned at him from within his helmet. “Onward to the moon! Right, Stewie?”

Stewie nodded eagerly but was overcome with sudden tears. There was the Earth, in full view. The rocket had turned in flight, and the entire globe was framed in Stewie’s portal. Its blue oceans and white clouds, its green expanses of new growth and brown desert. He turned away. It hurt too much to look at it.

Tears streamed down his cheeks inside the helmet. He panicked for a moment, wondering if you could drown in your space suit if you cried too much.

He realized, then, he was thinking about Dougie and Harold and Jack. The four of them had been a team for as long as he could remember. And his buds were still all there, back in the neighborhood where Stewie has lived his entire life.

He corrected himself in mid-thought: had lived, not has. Stewart doesn’t live there anymore. He’s no longer an Earthling. Now he lives on the moon.

The tears kept flowing, and then the snot started, but Stewart couldn’t wipe his face since his head was inside a glass globe. He bore down with as much resolve as he could muster and forced himself to stop crying. He had to do it, because what would Ruthie think if her big brother died on his first day in space by crying himself to death?

He dismissed the humiliating thought and tried to find a way to pass the time. It was going to be a long trip to the moon, Dad said. A very long trip. And he was right.

The colony at Tranquility Base turned out to be awful. When they landed, a greeter took them to their new home. It was way worse than the house they’d had in New Jersey. For one thing, he had to share a room with Ruthie, plus there was no vid screen. How much worse could it get than that?

In school, they learned about the first group of settlers who built the living modules and schools and shops. Everything was put beneath a big plastic dome.

“Those pioneers chose the place for our colony. It was called Mare Tranquillitatis,” his teacher said, the place where the first Apollo astronauts had landed, the place that people first set foot on the moon. “The flag the astronauts planted is still here, under its own little dome.”

Some of the bigger domes were where they made water and food. The biggest is the one over the seashore, where they’re now arriving. The rover enters the airlock, and when the inside door opens, the colonists disembark and shed their spacesuits.

“Let’s set up over this way,” Dad says, pointing. “Ruthie, want to build a sandcastle?”

Stewart rolls his eyes and flops down on the towel Mom has spread out for him. The place is depressing, a bunch of flat gray rock and fake overhead lights. In the middle of the stone plain sits a puddle of water, around which someone has spread a band of artificial sand.

Stewart pulls out his tablet and starts to play a game. The day drags on, worst Fourth of July in history. Hours later, the lights begin to dim. “It’s time!” Dad shouts, still as cheerful as ever.

Ruthie runs to sit on Mom’s lap. “It’s getting dark, Mommy,” she says. “Is it time for the fireworks?”

“It certainly is, sweetie,” Mom says. “Look.”

As Stewart starts to roll his eyes again, he catches a glimpse of what Mom is pointing at: overhead, a bright disc of blue. The lights grow dimmer and finally switch off, plunging the dome into almost total darkness, except for the brightness from that blue disc.

Stewart leaps to his feet. “Wait. Is that the Earth?”

Dad takes his hand and squeezes it. “Yes, Stewie. The big blue marble. That’s what we came here to see.”

Stewart is awestruck. He never knew the Earth was beautiful. He remembers the riots, which you can’t even see, and Harold and Dougie and Jack, and suddenly he’s crying again but he doesn’t know why.

“Aren’t there fireworks, Daddy?” Ruthie asks.

“They’ll do the fireworks later, sweetie. What do you think, Stew? Isn’t this the best Fourth of July you’ve ever had?”

Stewart turns away so Dad won’t see his tears, but now he knows what his life’s mission will be: he’s going back. And he’ll take Ruthie with him. Even if there are riots and fires, even if the enemy is still there fanning the flames, Stewart knows he has to return and help, knows that running away is no solution. He will always be an Earthling.

The End

Originally published in the June 2021 issue of Utopia Science Fiction Magazine

Before moving to the Washington DC area, Raima Larter was a chemistry professor in Indiana who secretly wrote fiction and poetry and tucked it away in drawers. Her work has appeared in Gargoyle, Chantwood Magazine, Cleaver, BULL, Linden Avenue, Another Chicago Magazine and others. Her first two novels, Fearless and Belle o’ the Waters, were published in 2019, and her nonfiction popular science book, Spirituality and the New Science, was published in May of 2021. Read more about her work at raimalarter.com .